Human interaction is constructed around texts.

Sometimes these are central universally-accepted texts. In Ancient Greece the texts were the works of Homer. In Rome, they were Homer and Virgil. For much of the last two millennia, Europe and America’s text was the Bible. In Jewish communities, it was the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) and the Talmud.

Texts serve as short-cuts. They provide us with ready-made phrases, metaphors and parables which are both accessible and instantly understood by the people we’re talking to. They give us a sense of shared consciousness.

In the 20th Century, our shared texts in English were Shakespeare and Dickens, and then the new media of cinema and television gave us new texts; the latest soap opera, drama or sitcom gave us our stock phrases and handy references – “it’s like that time on…”. You could watch the latest film or TV episode and talk about it the next day with your friends at work or school.

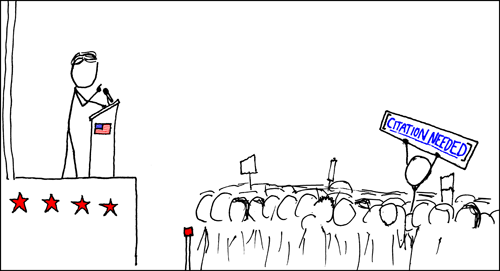

The Internet has changed some of that. There is too much text: too many videos, too many jokes and articles and comment threads; too many TV programmes to watch and books to download. Of course, the Internet has also spawned its own responses – memes and injokes that constitute their own sort of shared text – but these are all about form rather than content.

All of this is really cool, because instead of talking about things we all already know, we can share the new exciting stuff we read or saw or heard today. That’s great. But because it robs us of a shared text, it means we’re frequently making references that the other people in our conversation don’t understand.

Of course, this has always happened in some circles. People of different ages have different shared childhood and adolescent experiences, for example. An even more striking case is with people from different countries. I’ve spent enough time around Americans by now to get some of the references to Schoolhouse Rock and Twinkies, and here in Israel I am slowly picking up the society’s texts.

Frequently, then, I talk to friends and find myself referencing something that they don’t know about, whether it’s because they aren’t British or are a little older or younger than I or whether it’s just a video I saw that they didn’t or an article I was sent that they weren’t.

So I’ve started to keep a mental list during a conversation of all the things I’ve mentioned, suggested or referenced. Then, when I get home, I send footnotes – links, references, a little commentary. It’s becoming a habit and one that I quite enjoy, even if it does take a little time to curate the links.

Of course, I’ve no real idea if anyone actually follows all the material that I send them. I doubt it, because it can be a lot, with references to hundred-hour TV shows and weighty series of books – and who has that kind of time when all they wanted was to have a cup of coffee or go to a party – but I like the idea anyway, and it forces me to revisit the things I think I remember or know about, and sometimes reinterpret them altogether.

So, if I were to have a conversation with you, you’d send me a list of all the bits I didn’t get? Doesn’t that come over as just a bit patronising?